'The People are, under God, the Original of all just Power'

1648/9: a new English constitution takes shape

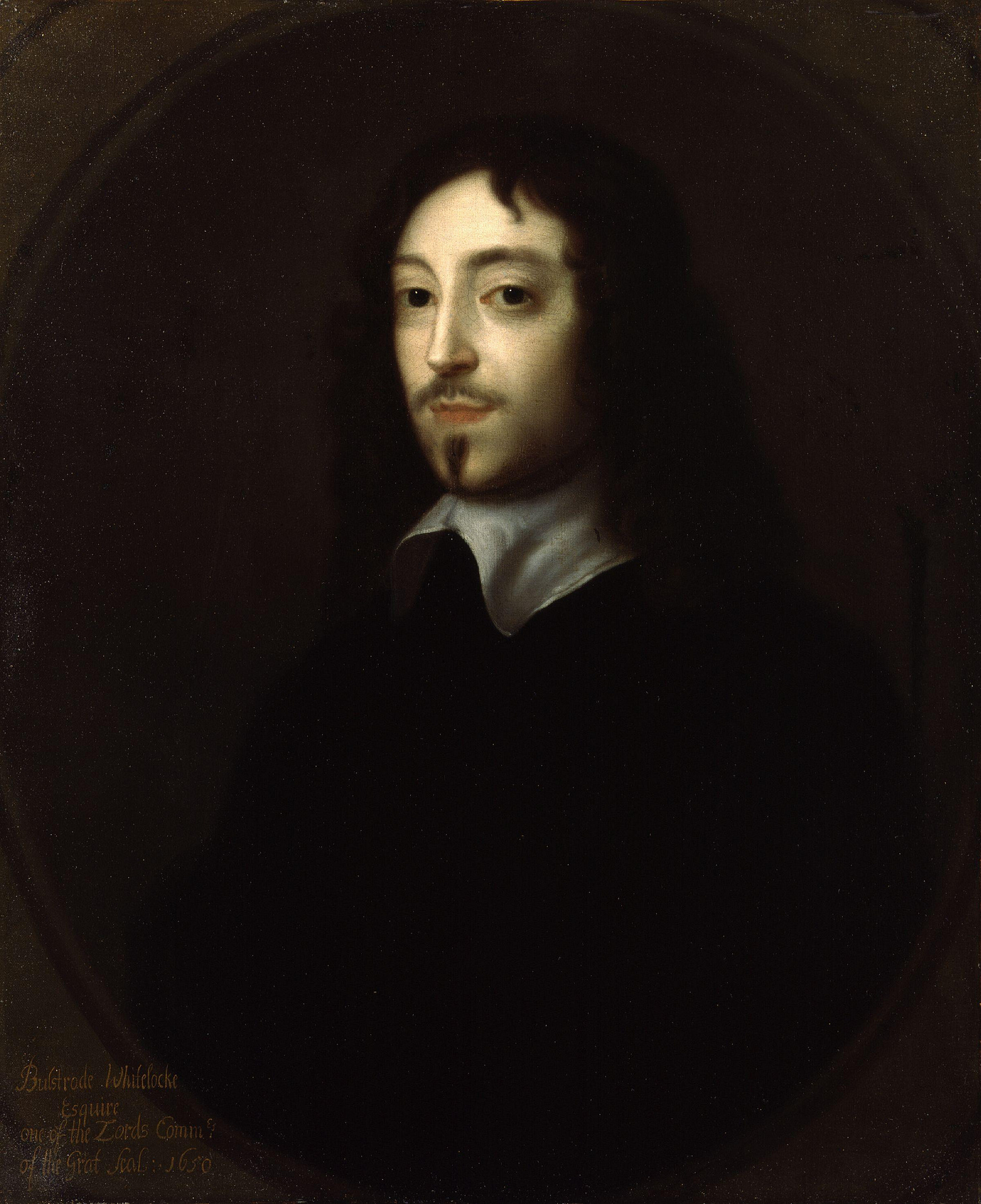

Portrait of Bulstrode Whitelocke MP. Around 1650, unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery, London. Public domain.

Constitutions are partly about the realities of power; and partly in our heads. How we think we are governed, what we think it was like in the past, and what we hope or fear for the future. All for better and worse… [This series seeks to offer] an examination of what people thought the position was at a particular time, how they thought they’d arrived there and where they thought things might be headed. And how that contributed to the reality of what they had, and what we have today.

That was what I wrote in the first piece in this series, on September 1, 2024. This second piece now seeks to start delivering on that promise.

England, March 1648/9

Let’s start with dates. In England in the seventeenth century, the year started on March 25, Lady Day.1 The period which contemporaries regarded as January 1 - March 24, 1648 is easier for us nowadays to think of as part of 1649.2 I’ll write such dates as 1648/9.

With that out of the way -

On March 22, 1648/9, Edward Husband, Printer to the House of Commons of England, published

‘A Declaration of the Parliament of England, Expressing the Grounds of Their Late Proceedings, and of Setling the Present Government in the Way of a Free State.’

This piece establishes the essential background to the Declaration, assuming very little knowledge of English history.

First, a very light summary of the years leading up to November 1648.

Then, a slightly closer look at the constitutional discussions and developments of the period December 1648 to March 1648/9.

The next piece, planned for October 1, 2024, will discuss the Declaration itself.

1600 - November 1648

In 1600, Charles Stuart was born in Edinburgh to the King of Scotland, James VI. In 1603, James also became King of England and Ireland and moved his family down south. Upon his father’s death in 1625, Charles became King of all three kingdoms.

England was by far the richest of the three kingdoms. For reasons we’ll explore at a later date, Charles summoned its Parliament to meet in late 1640. The English Parliament was a two-chamber legislature: a House of Commons and a House of Lords (or, as it was widely known then, House of Peers). Members of the Commons were elected - in 1640 there were 507 of them. The Lords compromised both temporal lords (such as barons and earls) and bishops - though the latter were excluded from 1642.

An Act of Parliament required a majority of both Houses and the assent of the King, which in those days was not just a formality. But there was an ongoing dispute as to the scope of the King’s power to act without the consent of Parliament, and in 1642, things had reached such a pitch that war broke out between the King and Parliament.

By 1646, Parliament had defeated Charles’s forces in England, thanks to its highly effective New Model Army and an alliance with Scotland. Charles surrendered to the Scots but in January 1647 they sold him to the English Parliament, who held him in Northamptonshire and sought to negotiate a settlement. Tensions existed between Parliament and Army, and in June 1647 the latter seized Charles, holding him eventually at Hampton Court, near London. Attempts were made between Parliament and the King to negotiate a resolution during this period.

Quite radical constitutional suggestions were made in the Putney Debates and the proposed Agreement of the People of October - November 1647. We’ll come back to them in later pieces. But for now, let’s just note that in November 1647, Charles escaped from the Army’s custody and made his way towards the stronghold of a sympathiser on the Isle of Wight, just off the English south coast. In fact, the supposed sympathiser was on Parliament’s side and held Charles (in comfortable quarters) on its behalf.

From his new custody, Charles stirred up a resumption of hostilities by forces sympathetic to him, including a secret agreement with a faction in Scotland who invaded England on his behalf in mid 1648. The New Model Army defeated the various English uprisings and the Scottish army by August of that year.

Despite that outbreak, the majority of Parliament still favoured negotiations with Charles. These continued from September to November 1648, exploring the possibility of Charles continuing as King with reduced powers.3 But trouble was brewing in Scotland and Ireland and Charles was evidently playing for time.

December 1648

When a majority of the House of Commons voted in early December 1648 to continue negotiations, the Army command decided that they had had enough.

Their first step was to ‘purge’ Parliament on December 6 - arresting (temporarily) some members who favoured engaging with the King and barring others from participating. The number of members was thus reduced to around 200, though only 50 - 60 subsequently took part in debates.

On December 13, this slimmed-down ‘Rump’ agreed to break off negotiations with Charles. The Army then brought Charles to London.

It appears from the memoirs of Bulstrode Whiteloke, a lawyer and Member of Parliament, that the Army leadership decided on December 23 that a settlement with Charles was impossible and that he should be put on trial for his life.4 The Army’s most important leader, Oliver Cromwell, remained a Member of Parliament and was closely involved in these discussions, as were others from the Army leadership and, in addition to Whitelocke, another lawyer-MP, Sir Thomas Widdrington.

It is important to know that Whitelocke’s memoirs were only published many years later at at a time when Cromwell and the other main Army leaders of 1648 were dead, and when Whitelocke had reason to distance himself from the King’s trial and execution. They are not fully reliable, but for these crucial days we have little else.

According to Whitelocke, it was not yet agreed among the Army leadership in late December whether to do away with Kings altogether or to remain open to one of Charles’s three sons being made King. He reports that one possibility considered was to crown the youngest, Henry, an eight year old in the Army’s custody ‘whom they could educate after their own fashion, and… might train up to be a constitutional King.’5

Whitelocke’s characterisation of what happened years later was that, after deciding to put Charles on trial, the Army then left Parliament to do their ‘most dirty work for them.’6 However you characterise it, the fact is that on December 26 a committee of the House of Commons was appointed to consider how to proceed ‘in a Way of Justice, against the King and other capital offenders’ and to prepare legislation for this purpose.7 Later on the same day, this committee was also instructed to ‘consider of, and present to the House, some general Heads concerning a Settlement’8 - apparently meaning a constitutional settlement.

Proposed legislation to establish the court to try Charles was considered by the Commons on December 29 and 30, which also resolved that ‘it is Treason in the King of England… to levy War against the Parliament and Kingdom of England.’9

January - March 1648/9

At the next session of the Commons, on January 2, 1648/9, the committee ‘appointed to take into Consideration the Settlement of the Kingdom’ was ordered to ‘meet this Afternoon; and… speedily present something to the House to that Purpose.’10 This haste was presumably prompted by knowledge of discussions in the House of Lords the same day. In any event, it was formally reported to the Commons the following day, January 3, that the Lords had unanimously rejected the proposed legislation to establish a court to try Charles.11

The Commons responded to that rebuff on January 4 by ordering the committee to make its report on the establishment of the court the next day, and by resolving that the Lords’ refusal of consent did not matter. ‘Three Votes’ were passed on January 4:

‘[T]he People are, under God, the Original of all just Power.’

‘The Commons of England, in Parliament assembled, being chosen by, and representing the People, have the Supreme Power in this Nation.’

‘Whatsoever is enacted, or declared for Law, by the Commons, in Parliament assembled, hath the Force of Law; and all the People of this Nation are concluded thereby, although the Consent and Concurrence of King, or House of Peers, be not had thereunto.’

Based on that assertion of authority, an ‘Act of the Commons of England assembled in Parliament’ was then passed by the Commons alone on January 6 providing for the establishment of a court to try Charles.12

In the following days, various steps were taken which appear to reflect a certain understanding of the constitutional direction of travel. The Commons committee resolved on January 9 that ‘the Name of any one Single Person shall not be used’ in certain formal legal documentation. On the same date, the Commons resolved that a new Great Seal should be created including the words ‘In the First Year of Freedom, by God’s Blessing restored, 1648.’13 And on January 13, the Commons resolved to remove the requirement for loyalty to the sovereign from certain oaths.14

The King’s trial started on January 20. He was found guilty and sentenced to death on the 27th then beheaded on the 30th. We’ll discuss that process at a later date. But for now, let’s pass on quickly and simply note that the House of Commons’ constitutional innovations started to speed up. On January 29, with the King already considered dead in law as a result ot his sentence, an Act was passed requiring all courts and judicial documents to replace references to the King and Crown with references to Parliament and Republic.15 And on January 30, with the King now dead in fact, the Three Votes of January 4 were confirmed and ordered to be printed, and an Act was passed to make it high treason to proclaim anyone King of England or Ireland.16 That said, the Act provided that such a proclamation would not be treason if done with ‘the free consent of the People in Parliament first had and signified by a particular Act or Ordinance for that purpose.’ So, the possibility of a new King was kept open.

Not for long though. A few days later, on 6 February, the Commons passed, without division,17 a resolution that the House of Lords ‘is useless and dangerous, and ought to be abolished: And that an Act be brought in, to that Purpose.’18 And the following day, February 7, the future of the monarchy was debated and it was resolved, again without division, ‘That the Office of a King in this Nation, and to have the Power thereof in any Single Person, is unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the Liberty, Safety, and publick Interest of the People of this Nation; and therefore ought to be abolished: And that an Act be brought in, to that Purpose.’ On February 8, the Court of King’s Bench started to be referred to in the House of Commons as the Upper Bench19 and in the following days various related changes of terminology were implemented.

Attention then passed to establishing a new executive government — a Council of State to replace the monarchy’s Privy Council. On February 13, it was announced in the Commons that a list of members was ready, and on February 14 the Commons approved the list.20

The idea of the Declaration mentioned at the start of this piece evidently arose around that time as, on February 16, a committee of sixteen members ‘or any four of them’ were ordered by the Commons to prepare

‘a Declaration of the Grounds and Reafons of the Parliament’s late Proceedings, and the Benefit redounding to the People of this Nation thereby.’

Whitelocke and Cromwell’s son-in-law, General Ireton (also a Member of Parliament), were the first and second named of the sixteen.

The Commons handled numerous matters of pressing day-to-day business in the following weeks, but on March 5 the Acts21 for abolishing the House of Lords and ‘taking away Kingship’ received their first reading in the Commons.22 On March 7, both were read a second time. Also on March 7, the Whitelocke / Ireton committee was ordered to present their proposed Declaration the Commons on March 12. They evidently failed to do so, because on March 14, the Commons ordered Whitelocke by name to present it on March 16.23 This time he did so, and it was recommitted to a smaller committee this time, again headed by him but with only six members, ‘any two’ of whom were to present an amended version. Whitelocke presented the amended version the next day, March 17, and the Commons approved it and ordered it to be printed.

The same day, the Act for abolishing the Kingly Office in England and Ireland was read for a third time and therefore (under the new constitutional understanding announced on January 4) enacted. The Commons also resolved to take down ‘the Place erected [in Westminster Hall’ for the Sitting of the late High Court of Juftice’ with the Courts of the Upper Bench (formerly King’s Bench) and Chancery being set up there again. A couple of days later, on March 19, the Act to abolish the House of Lords also received its third reading and thus enactment.

Next time

So much for background. I plan in the next piece, on October 1, 2024, to look at the text of the Declaration itself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Day

January 1 only became the first day of the new year in England in 1752. England also moved from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar at that time, ‘losing’ 11 days.

The Treaty of Newport. The castle on the Isle of Wight where Charles was being held is in the town of Newport.

For the sequence of events, see Fitzgibbons, Rethinking the English Revolution of 1649, The Historical Journal 60, 4 (2017), pp 889 - 914.

Whitelocke’s memoirs, p 254.

Whitelocke’s memoirs, p 253. The original spelling was ‘durty worke.’

See Journal of the House of Commons (JHC) for December 26, 1648 at vol 6, p 104 of the 1803 reprint for 1648 - 1651.

JHC p 105.

JHC pp 106 and 107.

JHC p 108.

JHC p 109 reporting the proceedings in the Lords the previous day:

‘Then the Ordinance for erecting a High Court of Justice for the Tryal of the King, was read the First time’

‘And the Question being put, Whether this Ordinance, now read, shall be cast out;’

‘It was resolved in the Affirmative, Nemine contradicente.’

The Hathi Trust has conveniently made available online the three volumes of Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum (A&OI) published by HM Stationery Office in 1911. See the “Act of the Commons of England assembled in Parliament for Erecting a Court of Justice, for the Trying and Judging of Charles Stuart' at A&OI vol I, p 1253.

JHC pp 114 and 115.

JHC p 116.

A&O I vol I, p 1262. References to the King were to be replaced with ‘Custodes libertatis Angliae authoritate Parliamenti,’ to ‘Juratores pro Domine Rege’ with ‘Juratores pro Re-publica’ and to ‘Contra Pacem, dignitatem vel Coronam nostram’ with ‘Contra Pacem Publicam.’ The first of those Latin phrases was contemporaneously translated into English at JHC, p 143 as ‘Keepers of the Liberty of England, by Authority of Parliament.’

A&O I, vol I, p 1263.

That is, without any objection from sitting members.

JHC, p 132.

JHC, p 135. There is a strange resonance with the 21st century English terminology of ‘Senior Courts’ and ‘Upper Tribunal.’

JHC, pp 140 - 141.

The modern distinction between Bill (proposal) and Act (once enacted) was not yet made.

JHC, p 157. Then as now, the first reading of proposed legislation is a formality when it is introduced, and it must be voted to be ‘read’ twice more to be considered as approved by the House of Commons.

JHC, p 163.

Fascinating first article. As this series develops, I am interested in learning whether events and beliefs in England are reflected elsewhere, especially in Europe. Consious that all this is happening very shortly after the peace of Westphalia

Excellent! As someone who throws around "Cromwellian" a bit, it's good to walk through the sequence of events. On another note, I really like the introductory note on the ways that constitutional thinking means. Thank you and keep up the good work.